So that was 2020. The first year of lockdown. The final year of Trump. The year the UK tumbled off the Brexit cliff. The year we had 73.000 people die of COVID-19 in the UK.

It was a year when I stopped wanting reading to be challenging and just wanted it to take me somewhere else. I set my reading challenges aside and tried to lose myself in books that absorbed my attention and kept me from thinking too far ahead.

I’ve picked my fifteen best reads of 2020, (10% of the total) by asking myself which books I’m most likely to look back on in a year’s time and say, ‘that book has a fond place in my memory.’

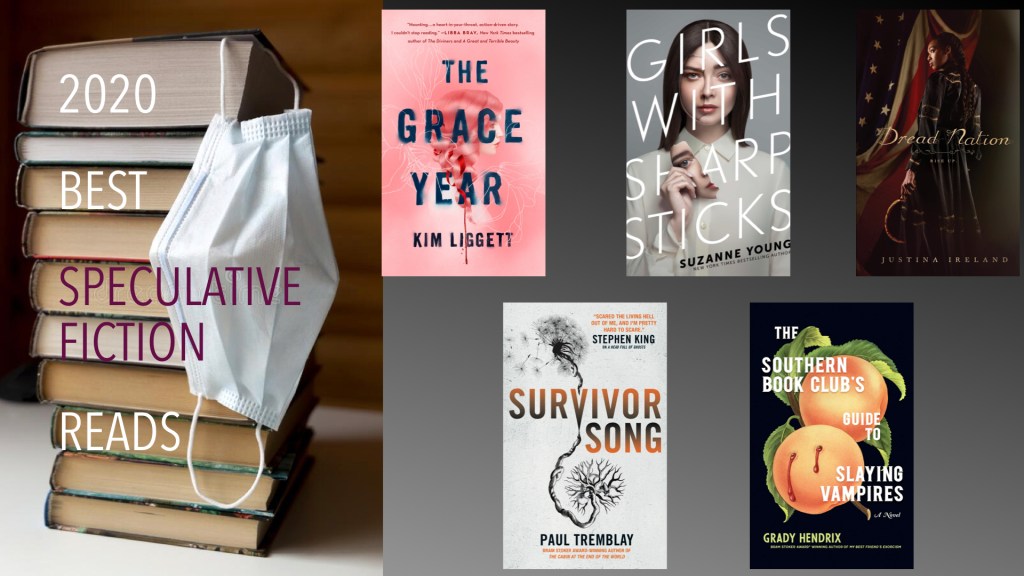

A third of the ones that made the cut are mainstream fiction. A third are speculative fiction with strong dystopian / anti-patriarchy themes The rest were science fiction and golden age mysteries.

I’ve kept the descriptions of each book short but provided a link to a full review in case you want to know more.

I’m grateful to these books. They helped me get through 2020. I hope there are a few here that you might enjoy in 2021.

‘Kitchens of the Great Midwest’ by Ryan Stadal (2015)

‘Kitchens Of The Great Midwest’ lived up to its catchy title and striking cover and delivered an accessible, memorable, moving story. The narrative, which follows the life of Eva Thorvald, from her conception to the to the apex of her career as a high-profile chef, is structured so that each chapter is focused on and told from the point of view of someone whose life has touched Eva’s. With every chapter we get a new character. fully and empathetically imagined and with their own distinctive voice.

As each person’s story is told, we get only the most indirect view of Eva, filtered through the passions and problems of the person the chapter is about but we get a deeply personal account of a key moment in each person’s life and what it means to them. Each character’s story is also linked to a dish which acts as a kind of emoji for the mood of the chapter. With each new dish we taste a new life and build up a sort of scent trail of intense flavours wrapped around memories of important moments.

‘The Weight Of Ink’ by Rachel Kadish (2017)

“The Weight Of Ink” follows two passionately intellectual women, Ester Velasquez and Helen Watt, separated by more than three hundred years but connected by words inked on paper and a need to know what is true.

Ester, orphaned in her teens, has been taken into the household of a blind rabbi and has moved with him from Amsterdam to 1660s London where, going against tradition, the rabbi permits her to become his scribe. In doing so, he ignites in her a hunger for the life of the mind which, as a woman, she should have no access to.

In 2000, Helen, sixty-four years old, in failing health and approaching a mandatory retirement that will end her career as a History Professor specialising in Jewish history, is invited by a former student to view a set of seventeenth-century Jewish documents that were discovered during a renovation of his house in Richmond. These papers lead Helen to piece together not just the truth of Ester’s life but of her own.

The writing is accessible, beautiful, calm and clear. I quickly found myself being immersed in the worlds of both of these women even though they were equally alien to me. Yet, by the time I was halfway through the book, I felt as if I had shouldered the weight of disappointment and sadness of each of the women. Ester and Helen are both serious, passionate, strong women who have few good choices available to them.

‘Fingerprints of Previous Owners’ by Rebecca Entel (2017)

”Fingerprints of Previous Owners‘ is an exceptional book: diverse, credible characters; beautifully crafted descriptions and perfectly inflected dialogue, and an innovative structure work together to deliver a view of the legacy of slavery, its modern faces and the ways in which a community descended from slaves deals with their heritage and their present challenges.

The novel shares the experiences, hopes, loves and frustrations of the people living on a small, formerly British, Caribbean island that once had a Plantation at its centre and the blood of slaves on its stones, and which is now dominated by a foreign-owned, American-run holiday resort, built on the site of the plantation.

Most of the story is told from the point of view of Myrna, a young islander who spends her days supporting herself and her mother by working as a maid at the resort and spends her nights using her machete to cut her way into the thornbush-choked inland in search of all the things the older generations refuse to speak of.

Myrna’s narrative was hard to take at times. While staying a very human, quietly told but emotionally rich story, it showed me the ways in which modern Corporate Colonialism carries the ethics of slavery with it. The removal of dignity. Turning local people into second class citizens. The assertion of the rights of the owners over the needs of the people. And the so-taken-for-granted-we-don’t-think-about-it racism. And none of it sounds like an exaggeration or a distortion. It’s simply a stark exposition of a global corporate culture that treats people as things.

‘Petra’s Ghost’ by C. J. O’Cinneide (2019)

‘Petra’s Ghost’ is an emotionally powerful book about guilt and forgiveness. It follows a recently widowed man as he walks the Camino de Santiago. Burdened by guilt over his wife’s death, he begins to doubt his own sanity and we are left to judge how much of his reality we share.

In the weeks after I read ‘Petra’s Ghost’, it haunted my imagination, showing me how real the journey along the Camino had felt to me and how invested I had become in the fate of the characters and most of all of how this portrayal of the challenges and possibilities of forgiveness had touched me.

‘Petra’s Ghost’ is hard to label. It doesn’t fit easily into a genre. It sets out to do something difficult and chooses a unique path to do it. It uses an unreliable narrator to show us and him the truth and it does the whole thing with wit and compassion,

‘Longbourn’ by Jo Baker (2013)

“Longbourn” tells the story of a young woman who makes the hard choices to win a life for herself and to share that life with the man she loves. No, her name is not Elizabeth Bennet. Her name is Sarah and she’s a maid at Longbourn. The story is mainly focused on Sarah, Mrs Hill, the housekeeper and James, the footman. The relationships between the three are deep and complex and entirely believable.

‘Longbourn’ is not an ‘Upstairs, Downstairs’ view of the Bennet family. The servants have their own lives. They’re dependent on their employers and very much in their power. The people upstairs mostly cause problems for or mess up the lives of the people downstairs (Mr Bennet and his affair with Hill and Wickham and his predation on Polly and threat to James). Perhaps worse than that, some of the people upstairs don’t see the servants as real or even don’t see them at all.

It seems to me that “Longbourn” wasn’t really was an Austen adaptation, it was historical fiction grafted on to Pride and Prejudice like grafting one apple tree onto another. Pride and Prejudice is the rootstock that provides a good environment in which the graft can flourish but the graft is the prize.

‘The Bone Clocks’ by David Mitchell (2014)

‘The Bone Clocks’ is astonishingly good. The audiobook was twenty-four hours long and I enjoyed every minute of it.

David Mitchell has managed to go toe-to-toe with modern fantasy writers in terms of creating supernatural beings and magical systems and a long struggle between darkness and light. Then he’s raised the game by embedding the story in a vividly evoked past and a credible near-future and telling it all through the eyes of engaging, credible, memorable characters.

David Mitchell let me take up residence in the heads of people who were very different from each other and often only loosely associated with one another and I believed in each of them, even the ones I didn’t like. In one case he let me occupy the head of the same person when they were in their teens and in their sixties and succeeded in showing me that they were and weren’t the same person.

The book goes from the nineteen eighties to the twenty forties. Capturing the decades that I’ve already lived through so accurately meant his descriptions of the parts in the future felt real and prophetic.

‘Planetfall’ by Emma Newman (2015)

‘Planetfall’ is a future SF classic with ambitious storytelling, insightful characterisation and a unique premise.

The storx is told from the point of view of Ren, a cripplingly anxious woman, struggling with guilt for a past decision not yet fully revealed but which we know involves colluding in a lie at the foundation of a colony on an alien planet, a lie which, twenty years later, is in danger of being exposed.

The story, which occurrs mostly in the present but includes some of Ren’s dreams and memories, tells of a trip to stars, led by The Pathfinder, to an unexplored planet on which they find a large organic structure that they refer to as ‘God’s City’.

The power of the book comes mostly from the intimate portrayal of Ren’s journey, or perhaps her pilgrimage, motivated by love and faith, hindered by self-doubt, broken by a single event and the lies that followed it, crippled by guilt and struggling painfully towards hope.

Capturing this in any novel is an achievement. Wrapping it in a novel of planetary colonisation that is more a pilgrimage to meet God, is extraordinary. Inserting a seed of betrayal and deception at the heart of everything and revealing it slowly, like a dead body you can smell but can’t yet see, is inspired.

‘Light Of Impossible Stars’ by Gareth Powell (2020)

“Light Of Impossible Stars” is a deeply satisfying read that does something very rare: it ends a trilogy in a way that not only doesn’t disappoint but excites and surprises.

Like it’s predecessors, “Light Of Impossible Stars”t was a fast-paced, page-turning, epic science fiction story, crammed with original ideas and strong world-building, yet what kept me reading were the characters in the book and the empathy and humour of the writing.

All of the books in the trilogy have followed multiple storylines that slowly reveal the big picture. The strength of the characterisation, especially in this final book, kept those storylines intimate and relevant.

Gareth Powell is very good at letting his characters be themselves, without judgement or apology, whether the character is a genocidal psychopathic poet, a warship who has grown a conscience and resigned her commission, a non-human engineer who believes in work and rest and the world tree, a young woman trying to discover who or what she is, or an ex-military officer looking for redemption through service.

‘The Body In The Library’ by Agatha Christie (1942)

What a delightful surprise ‘The Body In The Library’ turned out to be. Written seventy-eight years ago, it still feels modern and fresh. It’s brimming with energy, humour, and sharp observations and has a twisty plot that kept me guessing right to the end.

I think the thing I enjoyed most about the book was the humour. From the start, ‘The Body In The Library’ reads like a rather droll assault on the more ridiculous elements of detective fiction combined with wickedly accurate evocations of what she calls ‘the ruling class of censorious spinsters’.

I’m now a confirmed Jane Marple fan. I love that Jane is driven by insight into people’s wickedness, frailties, vanities and self-deceptions, with empathy coming almost as an afterthought and only then for people that she sees as innocents. I realised that I wouldn’t want to meet her unless she was on my side and even then, she’d know things about me that I don’t even admit to myself.

‘Miss Pym Disposes’ by Josephine Tey (1946)

In “Miss Pym Disposes”, Lucy Pym, author of a best-selling popular psychology book, is invited by an old school friend to speak at a prestigious girl’s physical education college which the friend now runs. She quickly becomes absorbed in the cloistered bu intense life of the college and finds herself faced with a difficult choice related to a death at the college.

Although it’s seventy-four years old, “Miss Pym Disposes” felt fresh and innovative and relevant. It never took the traditional path for a mystery novel and yet it managed to be tense and intriguing. It was filled with humour and with the honest human reactions rather than crime detection tropes.

‘The Grace Year’ by Kim Liggett (2020)

‘The Grace Year’ is a dystopian novel that manages to be both a deeply thought-through vivisection of what patriarchies do to women to keep them powerless and an action-packed, character-driven thriller filled with intense emotions.

We know from the first page what the Grace Year is supposed to be. Tierney, the narrator, tells us:

‘No one speaks of The Grace Year. It’s forbidden. We’re told we have the power to lure grown men from their beds, make boys lose their minds and make the wives mad with jealousy. They believe our very skin emits a powerful aphrodisiac, the potent essence of youth, of a girl on the edge of womanhood. That’s why we’re banished for our sixteenth year, to release our magic into the wild before we are allowed to return to civilisation.

The first half of the book, which does the initial world-building and describes the first few months the girls spend in their Grace Year was so thick with fear, rage, spite and betrayal that it was emotionally exhausting to read. The patriarchal cage these women are raised in is wrought in a fine filigree of taboos, violence, public shame and private unvoiced rage but it’s as nothing compared to what the women are willing to do to each other when they’re alone in their Grace Year.

In the second half of the book, Kim Leggit changes the pace. I won’t share the plot details except to say that what happens next goes beyond and comparison to ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ and ‘Lord Of The Flies’ (Ligett has quotations from both prefacing the book). What Tierney sees over the remainder of her Grace Year changes everything: what she wants, how she sees the other girls and it fuels her rage at and contempt for the men who placed them all in this situation.

The ending is… well, I was on the edge of my seat, desperate to know what the ending was. The short answer is ‘very satisfactory’. It has the punch of a thriller with a brilliant denouement but it also has a deeper level of thought that gives an insight into how women, stripped of overt power, will still work together to nurture hope and find limited freedom through subversion.

‘Girls With Sharp Sticks’ by Suzanne Young (2019)

‘Girls With Sharp Sticks’ is about girls at the ‘Innovations’Academy’ who are being taught to be ‘better girls’, obedient, respectful, compliant and pretty. It’s the story of one of the girls, Mena, waking up to the fact that the Academy is not what it claims to be and claiming her rage at what is being done to her and the other girls at the school.

The plot and pace of this book make is a compelling, I-have-to-know-what-happens-next and Oh-no-they’re-not-going-to-do-that-are-they? thriller. The first person narrative lets us share Mena’s journey, investing the reader in Mena’s struggle and binding us to her emotionally. It also lets the reader see, and often rage at, the gap between what Mena sees as going on and what we think is happening.

If you’re looking for a light, exciting, speculative fiction read, ‘Girls With Sharp Sticks’ will deliver it to you but along the way, my guess is that you’ll also find that you’re reading something that challenges the humanity of patriarchal misogyny and makes you question what a ‘better girl’ would really be like.

‘Dread Nation’ by Justina Ireland (2019)

‘Dread Nation’ turned out to be as cool and original as its cover. Set in in an alternate US where the Civil War was brought to an inconclusive close when the ‘Shambler’ dead started to rise and feed upon both armies, it tells the story of irrepressible negro girl called Jane McKeene.

Jane is almost ready to graduate from ‘Miss Preston’s School of Combat for Negro Girls’, after which she expects to find work as an Attendant assigned to defend a rich white woman from shamblers and inappropriate male attentions. Instead, she ends up on an involuntary journey that keeps her in constant peril from the dead and from the living.

‘Dread Nation’ manages to be a lot of fun while avoiding being light-weight fluff. Jane is a remarkable creation: intelligent, resilient, brave and holding back a mountain of rage. Like the book, she is full of dry, angry humour, most of it directed at the dangerous stupidity of bigotted white men too convinced of their own superiority to protect themselves from threats.

The story moves along at a clip, with smooth, effortless world-building delivered as part of a tight plot where current actions are set in context by old letters between Jane and her mother. I found myself wanting to turn the pages to see what would happen next but most of all I wanted to learn more about the irrepressible Jane.

‘Survivor Song’ by Paul Tremblay (2020)

‘Survivor Song’, is an intense character-driven story of two women struggling to survive as a deadly, fast-spreading virus washes across Massachusetts. Hospitals are overrun, there are shortages of PPE for front-line medical staff, disagreements between Federal and State authorities on what needs to be done, a struggle to impose a quarantine and small groups of self-appointed alt-right militia patrolling with guns.

It turns out that the virus is a form of fast-acting rabies, passed on by saliva. Within an hour of being bitten, people go rabid, lose their minds and start to bite others. Yep, you got it, a zombie plague.

But Paul Tremblay refuses to go down the route set out for us in all those zombie-apocalypse TV shows and video games. He keeps the focus human and real. He lets us continue to see the infected as victims, people who have been bitten and are losing themselves. He rejects the it’s.-the-end-of-the-world-so-let’s-abandon-civilization-and-kill-stuff knee-jerk reaction and frames the plague as something that will pass, something that can be survived, something where what we do and what we refuse to do to survive will define our futures.

As I neared the end of this book, with my emotions wrung-out, my mind buzzing with questions about what I’d do in these circumstances and with new real-to-me characters taking up residence in my memory, I tried to name what Paul Tremblay was doing to me, the kind of fear he’d been feeding me or letting feed on me.

It wasn’t horror, that hair-standing-on-end from a nameless fear feeling. It wasn’t terror, where the fear is like a pain so intense and overwhelming there is no room for anything else, not even the belief that it will pass. It was dread, the slow-burn cousin of the fear family. The one you see coming. The one that leaves you with your ability to think and act but slowly, inexorably extinguishes your hope.

What gives ‘Survivor Song’ extra bite for me is that it captures and amplifies the car-crash-in-slow-motion that has become daily life under COVID-19. The ending of the book goes a little beyond the car-crash of the plague. In some ways, it can be read as hopeful but I found it mostly sad. The survivors have a future but it’s a future salvaged from the wreckage of another generation’s dreams. It’s a message that survival has a cost and survivors have scars but they make other people’s future possible.

‘The Southern Book Club’s Guide To Slaying Vampires’ by Grady Hendrix (2020)

‘The Southern Book Club’s Guide To Slaying Vampires’ is a much darker and deeper book than the title had led me to expect.It’s set in the American South in the 1980s and tells the story of a vampire preying on a small community of women who meet each week in a book club to discuss books about serial killers.

Hendrix’s vampire is an embodiment of insatiable male greed. He’s charming and charismatic, has the knack of making the men around him want to follow him and feel better about themselves for doing so, even as he takes every opportunity, politely and with a smile, to undermine, demean, mock and threaten their wives. He is a corrupter, a sower of discord, a parasite.

Hendrix’s vampire isn’t some stuffy Transilvanian Count pining for his glory days, he is 100% Pure American Prime Raggedy Man. He’s the hustle that has always sold the American dream without ever delivering it.

What I liked most about the story was its message that knowing the vampire is there, knowing who he is and what he does, isn’t enough to defeat him or even to convince the people who love you to help you because this vampire has seduced not the women but the men. He’s turned them into the worst version of themselves and used them as a rod to impose his authority. Any woman who stands against him risks losing everything and with no guarantee of success.

One thought on “2020 Best Reads”