John Joseph Adams wants the climate change stories in “Loosed Upon The World” to:

“serve as a warning flare, to illustrate the kinds of things we can expect if climate change goes unchecked, but also some of the possible solutions, to inspire the hope that we can maybe still do something about it before it’s too late.”

I bought the anthology because the first story is “Shooting The Apocalypse” Paolo Bacigalupi.

I was introduced to Paolo Bacigalupi by his astonishing book, “The Windup Girl” set in a future Thailand which is under constant threat of flooding.

What made him a must-read writer for me, was his book, “The Water Knife”, set in a fractured future America, devastated by storms and desperately short of water.

To stem the tide of climate migrants, especailly from Texas, movement between the States is now illegal. The story focuses on the fighting between Nevada, Arizona, and California for control of the ever dimininishing Colorado River.

It’s a horribly plausible, fundamentally brutal world in which, as his main character explains:

“Some people had to bleed so other people could drink. Simple as that.”

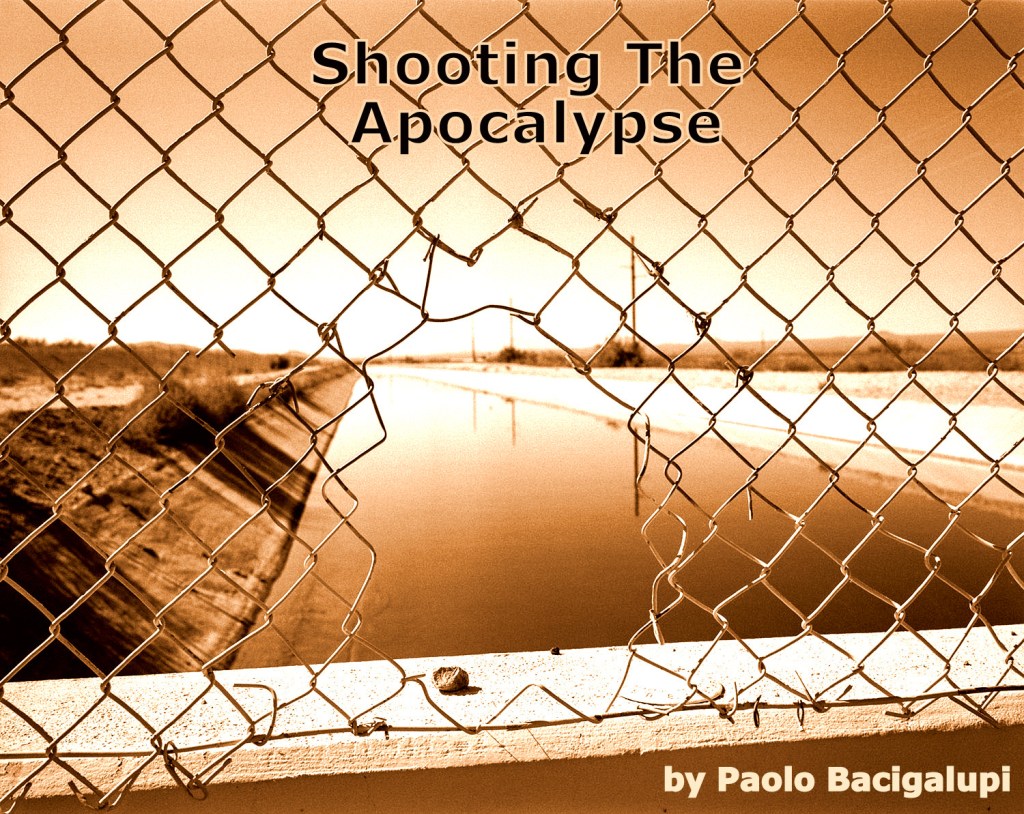

“Shooting The Apocalypse”, set in the same future as “The Water Knife” follows a local photographer and an ambitious Northern journalist as they follow up on what they hope will be the story that makes their careers.

The story centres on the CAP (The Central Arizona Project), a huge canal that brings water through the desert from Colorado to Arizona and the things people are willing to do to protect the water they have from those who have none.

The writing is muscular and unflinching in the way that it confronts the violence produced by anger and fear. The hardening of attitudes and the lack of empathy described is grimly convincing but the real push of the story is to show us how rarely we choose to the see things as they are and then act on what we see. Instead of seeing things how they are and adapting to them, we remember how they have been and try to retain or rebuild as much of the old world as we can, no matter how infeasible that is.

One of the groups trying to escape from a clear vision of reality is the refugees, mostly from Texas, who have lost everything and are welcome nowhere. They are “ministered” to by a group nicknamed the Merry Perrys, who prescribe a form of roadside spiritual aid that is big on buying friendship beads and earning salvation through repentence. Timo, the photographer, recalls doing a story on a Merry Perrys meeting. He remembers the…:

“…tent walls sucking and flapping as blast-furnace winds gusted over them. The dust-coated refugees all shaking,moaning, and working their beads for God. All of them asking what they needed to give up in order to get back to the good old days of big oil money and fancy cities like Houston and Austin. To get back to a life before hurricanes went cat 6 and Big Daddy Drought sucked whole states dry. “

Of course, there are downsides to seeing the world too clearly for too long. Reality tends to break the polite pretences that allow people to spend time together.

Timo knows how this works. At one point, he loses his temper with Lucy, the Northern journalist because he thinks she’s playing him. He calls her on it and she stalks off in anger. Then Timo tells himself…

“She’ll cool off, he thought as he let her go. Except maybe she wouldn’t. Maybe he’d said some things that sounded a little too true. Said what he’d really thought of Lucy the Northerner in a way that couldn’t get smoothed over. Sometimes, things just broke. One second, you thought you had a connection with a person. Next second, you saw them too clear, and you just knew you were never going to drink a beer together, ever again.”

It may seem that Bacigalupi is not offering any solutions to the problems that he’s describing. The lives of the people in his story are brutal. There is nothing soft or hopeful about them. Yet, I think he is offering something important. He’s showing us that we are all weaker if we cling to the idea that we can somehow get around climate change. The shift, when it comes, will be fundamental and irreversible. The future goes to those who adapt and move forward, not to those who bemoan what they’ve lost or who try to create pockets of wealth where they can pretend nothing has changed.

This is an excellent start to the anthology. If the rest are of the same quality, this will be a classic collection. It’s also likely to be one that alters my perceptions and priorities.

5 thoughts on ““Shooting The Apocalypse” by Paolo Bacigalupi – first story in “Loosed Upon The World” anthology”